The most repeated accident

Recently, Fireboss landed on the runway with its gear up while fighting a fire in Coimbra, Portugal. Over the past 18 years, the same organization has experienced seven similar incidents. Three of these occurred on water, posing significant risks to the pilots’ lives. The other four were minor runway incidents, causing only damage to the floats’ undersides. This situation, while disruptive for the airport and ATC, was not as severe. A similar event is shown in the following video, where a Canadair 215 experiences a gear-up landing but performs a go-around instead of stopping.

Here are the official reports of the four reported accidents.

- Gear down for water landing 3: (English)

- Gear down for wáter landing 2: (English)

- Gear down for wáter landing 1: (English)

- Gear up for runway landing 1: (Spanish)

As for the remaining three, they were either not reported or not investigated by the accident investigation boards. But we know and we have taken notes.

Accident rates

The first question that comes to mind is: Are 7 repeated events in 18 years too many for the same organization?

At first glance, it appears that yes, but we need to measure accidents against flying hours to draw reasonable conclusions.

Analysis of aviation safety becomes more meaningful when accident statistics are matched with flight hours. Fleet utilization is considered when calculating accident rates, which are expressed as accidents per 100,000 flight hours. This method allows for accurate year-to-year comparisons.

The following example from Safety Study NTSB/SS-01/01 illustrates this approach.

Considering the limited studies for General Aviation and Aerial Work, let’s estimate the approximate number of hours flown by the Fireboss fleet over the 18-year period to compare with the industry average.

In firefighting, the average contract for a specific aircraft ranges from 120 to 180 hours per season. During busy seasons, aircraft usage can increase significantly. For example, in 2013 in Portugal, six aircraft accumulated 1,195 hours over 360 sorties and 5,141 drops. Conversely, during less demanding seasons and locations, aircraft might fly less than 100 hours, sometimes as few as 50 hours. I was there from 2011 until 2019.

A reasonable estimate would be an average of 120 hours per year. This aligns with my personal pilot logbook, covering 16 seasons as a firefighting pilot for various operators in different countries.

Regarding the number of planes for the organization in question, they started with a couple of planes and grew to 10-12 units during the busier seasons, operating across Spain, Italy, and Portugal. Therefore, an average of 8 units operating every year sounds reasonable. At 120 hours per year per aircraft, over 18 years, this brings us to an estimated 17,000 flight hours.

Using simple math, we find that 7 accidents / serious incidents occurred over 17,000 hours, resulting in approximately 41 per 100,000 flight hours.

It’s important to note that these 41 events would pertain to one specific category, wrong landing configuration. Depending if it happens on the runway or on the lake, the damage would classiffied it as serious incident (runway landing with some damage to floats) or accident (water landing involving a wrecked aircraft). But the fact it happens during runway landing or scooping is just random, and we should stick to the worst case and imagine that it could happen on the water, destroying the aircraft and potentially killing the pilots. To me, accidents.

There were other events in different categories such as LOC-W (loss of control in water) during scooping, and recurrent wire strikes, as I recently described. Therefore, the 41 accidents could easily be doubled or tripled, potentially reaching 100 accidents or more per 100,000 flight hours.

When we compare 41, or 100, to the 7.2 rate of general aviation over 20 years ago, as shown in the chart above, or to the 0.27 rate of airlines (Part 121 – scheduled air carriers), we begin to understand where we stand.

The following chart from AOPA confirms that the general aviation (GA) fixed-wing safety record tends to stay between 6 and 7 per 100,000 hours flown.

Copyright AOPAAnd recent years has significantly improved. For instance, in 2018, the overall accident rate was 4.56 per 100,000 flight hours, and the fatal accident rate was 0.74 (Your Freedom to Fly). According to the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) and their latest Air Safety Institute reports, the overall accident rate for general aviation in 2021 was 4.28 accidents per 100,000 flight hours, with a fatal accident rate of 0.77 per 100,000 flight hours (General Aviation News) (Your Freedom to Fly).

In light of this, yes, it’s quite a lot for an organization, and it’s worth looking into as it shows systemic issues.

Apples – Barrels and Hanlon’s Razor: Tracking Down the Root Cause

The Bad Apple

Do we think all those pilots involved in the accidents were untrustworthy or stupid?

Having known them all, I can confirm they are far from stupid; some were they were indeed among the best cohorts the organization had.

If the organizational safety culture is still developing, we might tend to assume that the organization’s complex systems would be perfect if not for some untrustworthy or just plain stupid people causing procedural drifts.

This is known as the Bad Apple Theory.

But this does not seem to be the case.

The Bad Barrel

When an accident repeats over and over without effective barriers in place, we need to examine systemic and organizational issues.

The barrel could be rotten or in a bad state, contaminating the good apples.

Employees of a company are not inherently ethical or unethical but are influenced by the corporate culture and procedures.

People don’t go to work to perform poorly or cause accidents, except for violators who should be filtered and detected during selection processes.

In the accident “Gear Down for Water Landing 2,” the pilot was and remains a good friend—a great pilot. Following the accident, he was silenced with the statement, “this shouldn’t happen,” preventing us from learning from the incident. We only heard his comments off the record.

A few years later, during “Gear Down for Water Landing 3” another pilot, also a good friend and excellent pilot, faced the same issue. Once again, we couldn’t glean much from the incident, and no significant procedural changes were made, leaving us far from addressing the root cause.

Hanlon’s Razor

Why is the barrel rotten? Why aren’t the issues fixed? Is it because the people in charge are nuts or malicious?

Probably not.

The normalization of accidents every season might lead many to blame the showrunners (including myself sometimes). But a more realistic approach makes me think, that while they bear responsibility, it might not be in the way we initially think.

Nowadays, I prefer to keep some distance from these sort of organizations. Instead of believing they always act deliberately or engaging in an unwinnable moral debate, I hold onto some faith and drive by applying Hanlon’s Razor: we should not attribute to malice what can be more adequately explained by ignorance.

No conspiracy, no evil.

In other words, while the leadership team is enjoying promotions and the satisfaction that comes with the massive expansion we are experiencing, there are challenges that indicate a need for less celebrating and more effective guidance. As we’ll discuss in the next point, mitigation.

Mitigation

As mitigation after the last gear-up runway landing, the organization added extra flybys before a runway landing if the group splits and pilots end up flying alone. And a radio to the ground operator to perform a crosscheck.

Imagine an Iberia, Air France, or American Airlines aircraft performing a routine low approach and go-around to cross-check with the tower that they did not forget the gear down. Probably not the most effective way to tackle the issue.

Before that, they implemented a solution involving a sticker on the flaps. Since there is no flap indicator in the cockpit and the flap setup is done visually, they thought that reading a”Check Gear” sticker on the flap would solve the problem.

Surprise, surprise, the idea did not work.

The procedure to check the landing gear is a memory scan flow, repeated as a crosscheck between aircraft flying in the same group. However, this system has not been successful. When pilots speak, they don’t always look, and when they do, they aren’t always seeing. There is a difference between looking and seeing.

We know pilots had trouble seeing and identifying the landing gear indicator, and there were recommendations from authorities to train them more effectively.

Why would they see the sticker if the problem is not what they check but how they perform the check?

Their approach uses the same tools that did not work in the past to fix the symptoms. And most likely this issue will continue to repeat in the future.

The solution

It is called a checklist, and it has been around forever. If you are used to another type of aviation, it might seem strange that there is no checklist and everything is done by memory.

There is an inherited belief that checklists are not necessary for single-engine low-level aircraft because there isn’t time to read them. This is true for emergency procedures, as even official Air Tractor literature suggests.

However, for normal procedures, we can develop an abbreviated checklist in the form of a flip card that is easy to see and follow.

In our operational checklist (flip card), we should determine what are the less relevant points, the killer items, what flow makes more sense, which items should be “Read & Do”, and which ones can remain in memory. The items that must be crosschecked within a formation or group of aircraft should also be clarified.

Checklists should be brief. Overpacking will result in not being used or being vomited without proper checks.

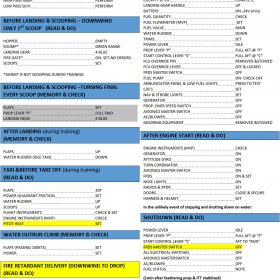

Here is an example of a self-explanatory flip card that was implemented on a new operator, where we were able to start the operation from scratch, leaving inherited paradigms behind.

The blue is the flip card for water operations and fire. The green is the flip card for land operations when interacting with a runway.

This part, extracted from the flip card is of utmost importance:

It must be crystal clear how we wish to operate through the checklist: what to read and do, what to check from memory, and what to crosscheck between aircraft.

The old-school way of thinking is rooted in the agricultural view when aircraft were simpler and scenarios were different. Flying a single-engine air tanker locally is not the same as operating a group of amphibious scoopers overseas.

The field of human factors psychology has conducted extensive research on checklist design and effectiveness. A key component of human factors research is looking beyond specific technologies to the guiding principles that govern human behavior. CRM (Crew Resource Management) and non-technical skills play a much more substantial role, as do checklist procedures and their training.

Therefore, pilots should be trained on checklist procedures to ensure they are aware of their systems (looking but also seeing) or intentionally interrupting them so they will start over.

No checklist, and it will bite you sooner or later. You are not different from all those who have bitten the dust (or swallowed water in this case).

Recommended related read:

“The Checklist Manifesto” by Atul Gawande shows how using checklists in complex environments can improve decision-making and reduce errors. Gawande, a renowned surgeon, explores how checklists, despite their simplicity, have a big impact on fields like medicine, aviation, and construction. Through compelling stories and research, Gawande demonstrates how these simple tools help manage complex tasks, ensuring that critical steps aren’t missed, improving overall performance, and reducing failures. The book encourages using checklists as a practical strategy to handle the demands of modern life and work, highlighting their power to boost performance and prevent mistakes.

Soft skills – CRM

Here is an example, extracted from a competence-based program, on how to train those specific CRM items:

If during the training or the supervised real operation, the pilot gets caught speaking but not looking, or looking without awareness, not seeing things, I am sorry but you are not competent yet.

The same thing goes for not managing to recover effectively from interruptions, distractions, variations, and failures.

In summary:

There is a lot more going on than individual mistakes, as you can see.

- In an organization, safety culture determines performance and results.

- Once the modus operandi is well established, it’s easier for an individual to be influenced by the culture than for the wrong culture to be changed.

- The old-school way of thinking is rooted in the agricultural view when aircraft were simpler and scenarios were different. Flying a single-engine air tanker locally is not the same as operating a group of amphibious scoopers overseas.

- The field of human factors psychology has conducted extensive research on checklist design and effectiveness. A key component of human factors research is looking beyond specific technologies to the guiding principles that govern human behavior. CRM (Crew Resource Management) and non-technical skills play a much more substantial role, as do checklist procedures and their training.

- “The Checklist Manifesto” by Atul Gawande shows how using checklists in complex environments can improve decision-making and reduce errors. Gawande, a renowned surgeon, explores how checklists, despite their simplicity, have a big impact on fields like medicine, aviation, and construction.

- It must be crystal clear how we wish to operate through the checklist: what to read and do, what to check from memory, and what to crosscheck between aircraft.

Let´s keep dry out there, and our keels unscratched!

2024 update:

After this article, we have been made aware of the following related incidents and accidents, including 3 more Gear up for runway landing, 2 of them, to the same organization, increasing to 9 the times this sort of incidents / accidents have happened to the same organization.

- 2023: 4th of February. Hard water landing simulating engine failure on dual seater trainer EC-LHI leaving the aircraft AOG for months. Same organization

- 2023: Turkish season. Wrong Landing gear configuration. Gear up for runway landing. There is no public report of this event. Same organization

- 2023: Wrong Landing gear configuration in Ibiza, Spain. Gear up for runway landing. Link here

- 2024: Tree impact during the approach to the lake Sao Pedro do Sul, Portugal on dual seater trainer, damaging the leading edge of the aircraft. There is no public report of this event. Same organization This ocurrence is not listed and it happened during the training process of a well known organization that has reported buying 12 Fire Bosses

- 2024: Turkish season. Hard runway landing short of the runway snapping landing gear configuration during a training flight. Gear up for runway landing. Same organization. There is no public report of this event, just pictures showing the damage.

- 2024: 22nd of July. Eslovenian season. Wrong Landing gear configuration. Gear up for runway landing.Same organization. Link here