Pilot Induced Porpoisng – Amphibious Scoopers

Ready to get off the waves of porpoising and ride the waves of knowledge?

Hold on tight, because we’re about to make a splash with a touch of humor on an important message.

Today, I want to dive into the exhilarating world of amphibious scoopers, specifically the art of scooping water effectively with the AT802 Fireboss.

You might have landed here after reading this introduction LinkedIn post. If not, you might want to start there to understand the context better and enjoy others’ comments and insights on the video below.

Now, let’s get down to business.

Picture this: You’re called to a fire in your majestic AT802 Fireboss, that aircraft that is in fashion, and everyone seems to want to fly these days.

You perform the first drop and head to the lake.

It’s time to switch from being an airplane to a weird speed boat. Yes, we’re talking about water collection, also called scooping, that magical moment where the sky meets the water.

For sure, one of the most interesting things I have done as an aviator!

Scooping and pilot-induced porpoising

One of the telltale signs of a clean scooping technique is a steady nose throughout the entire maneuver. It’s like gracefully gliding on water, making it look effortless.

But here’s the flip side: a phenomenon called porpoising.

Nope, porpoising is not some aquatic dance move. It’s a rhythmic pitching motion that turns your elegant water collection into a wild rodeo ride (according to some Fireboss pilots).

Trust me, it’s not a performance you want to showcase! You will understand why when we get serious later on in this entry.

The word porpoising comes from the high-speed surface-piercing motion of dolphins and other species, in which long, ballistic jumps are alternated with sections of swimming close to the surface. The first analysis of this behavior (Au and Weihs, 1980) showed that above a certain ‘‘crossover’’ speed this behavior is energetically advantageous, as the reduction in drag due to movement in the air becomes greater

than the added cost of leaping.

This technique is 20-40% more efficient for certain cetaceans, but it is not the case for a float plane, even less for an amphibious scooper!

Let´s remember that we are not in our element, we have been doing this for less than 100 years while cetaceans and birds have been doing this for millions of years.

Effective scooping needs speed and stability, and you need as much speed as you can control!

For effective travel planning over water, speed, and stability are paramount. Any movement in directions other than forward translates to wasteful energy consumption. Energy spent on unnecessary oscillations like porpoising diminishes the forward propulsion energy. Additionally, regaining balance by manipulating controls not only depletes energy but also escalates drag, hampering our progress.

But remember that while scooping, we are not a good speed boat… nor a good plane!

Hydrofoils possess the capability to achieve remarkable speeds, with the fastest among them reaching over 50 knots. In the realm of waterborne crafts, planning is a mode of operation wherein the craft’s weight relies more on hydrodynamic lift rather than hydrostatic lift (buoyancy) to sustain itself.

That is what we do most of the time, with the assistance of our aerodynamic controls, using the air too, in addition to the water.

A matter of balance – the sweet spot:

An optimum scooping process involves preserving energy.

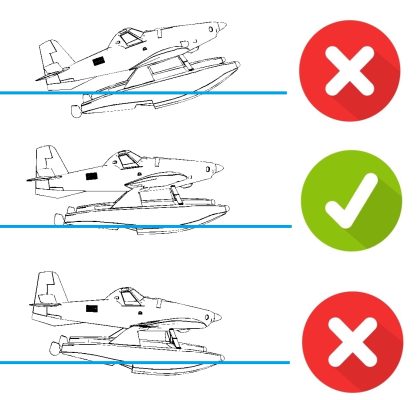

Maintaining a high nose is crucial to avoid the bows and propeller hitting the water. However, finding the optimal balance at each speed is vital to gain acceleration – what we like to call “The sweet spot”. It represents the point of least resistance for forward movement.

If the nose is excessively elevated, it generates a larger wave beneath the floats, resulting in heightened resistance. Lowering the floats’ angle diminishes this wave, reducing drag and enabling smoother acceleration.

But watch out, too low will get you in trouble too. If the nose is low and the plane is too fast for your current skill level, you will probably lose directional control. Once the rotation axis crosses the Center of Gravity, the plane behaves similarly to a tail wheel aircraft.

Tricycle vs Tailwheel…also on floats?

While using a tricycle gear plane, if the aircraft begins turning right on the runway, two forces come into play. Firstly, friction on the wheels causes the plane to turn right. Secondly, the center of gravity (CG) reacts by shifting in the opposite direction, aiming left.

However, due to the CG being positioned ahead of the main gear, these two forces counterbalance each other. Consequently, the plane tends to auto-correct, straightening itself and maintaining its forward roll down the runway.

While landing a tail wheel plane, if the aircraft initiates a right turn, we also have the same two forces at play. Firstly, friction on the wheels contributes to the rightward turn. Secondly, Newton’s third law prompts the center of gravity (CG) to react in the opposite direction, specifically towards the left, but there is no main landing gear close to it to counteract it as it happens with nose wheel aircraft.

Back to amphibious scooper and landing this nose wheel vs tail wheel stability concept:

While scooping slow (50-60Kts), the plane behaves like a docile nose wheel. Every input has a reaction, but slowly and forgiving. The energy we lost reducing to this speed from touchdown speed takes distance to come back before reaching lift-off speed. This is how we teach new pilots, it is not the most effective, but the safest.

While scooping fast, forces are magnified and the environment becomes less forgiving.

IMPORTANT!!!

Only go fast, into the second drawing shown above, once you are ready and have mastered the aircraft reactions at lower speeds.

I know pilots who were scooping too fast beyond their current skill level, and lost control of the aircraft. This has historically created a broad pool of stories and myths, linking this reaction to scooping asymmetries, or a mysterious sharp yaw…

Occam’s razor – A more simple and less mysterious reason:

As we anticipated above with conventional landing gear planes, when we go fast and the axis of rotation (that moves across the floats) is ahead of the CG, when we make even a small input, or stability is altered due to waves, wind, etc…Newton’s third law prompts the center of gravity (CG) to react in the opposite direction, but there is no main landing gear close to it to counteract, neither a fixed runway to grab our tires, we just have slippery floats without a fixed point of attachment.

The aircraft will lose directional stability in the same way a twitchy tailwheel would do if the pilot is slow to anticipate and correct.

But, the lower the speed the smaller the wave, and therefore less porpoising, right?

Au contraire mon frère.

At low speeds, floats are upheld by buoyancy, following Archimedes’ principle. However, as velocity escalates, intricate physical factors and the design of the floats prompt the creation of a hydrodynamic lift. This lift empowers the floats to ascend above the water’s surface, diminishing the area in contact with the liquid. Consequently, this reduction in contact area leads to smaller waves and decreased resistance, culminating in accelerated speed and swifter movement.

Porpoising is something we should fix

Now, here’s where things get serious. Porpoising is not just a fun bumpy ride, It’s a red flag.

As an instructor and examiner on the Fireboss, I have seen and studied quite a few cases where porposing developed into a LOC-W, losing both pitch and directional control and causing serious accidents. Remember that heavy water interaction and surfin´bird jumps on the water while loaded to MTOW will stress and fatigue the aircraft structure even if you can see it.

Porpoising can also cause a premature lift-off with an extremely high angle of attack, which can result in a stall and a subsequent nose-down drop into the water.

1/3 of the accidents were during the scooping phase and 12 had to do with a LOC-W (Loss of Control in Water) due to pitch or directional issues.

Here is another doxastic article diving into those types of accidents

To conquer the porpoising beast, and ensure a safe and effective scooping process:

- Touchdown at the right attitude and hold the nose into the sweet spot.

- Deploy the probes while adding the right amount of power to preserve speed. Keep being an aircraft working with the wind

- Provide timely and precise small counteractions with the stick further from where you were probably taught.

- Use your controls effectively, and anticipate stick inputs.

Yeah right… but how? Been trying but I am still all over the place.

Can we be more specific here?

Yes.

1: Regarding the flare: Think of a ratchet mechanism. Flare in stages and whatever you pull on the stick, does not come back forward. I see many pilots overreacting to the controls with last-moment forward inputs if they misjudged the flare. If you find yourself high, do not push forward, that will mess everything up, combining an increased sink rate with a flat touchdown (bad news). This will initiate porpoising. Instead, catch up with power while maintaining the nose position at the sweet spot.

A classic mistake and accident are continuing to pull on the flare, exceeding the sweet spot, then the critical AoA, stalling, and dropping one wing. That is one of the reasons we like our pilots to do UPRT, so they can recognize it, avoid it, and catch up with the opposite rudder if it happens, instead of correcting with the opposite aileron, which will make things worse.

Once touched down, hold the stick, or bring it slightly back, but do not be lazy letting it forward as with a runway landing. You will bounce on the bows and porpoising will start.

2. Oh that PT6-67F power quadrant on the Air Tractor….

One of the most common complaints of students is about the design of the power quadrant. Although it may not be perfect, we should learn to work with it precisely and efficiently. In my lessons, I teach students how to adjust torque within 3 seconds. We shouldn’t keep blaming the tool for its flaws. Instead, we should focus on training ourselves and fixing the issue. When adjusting forward, it’s important to end with a gentle touchback to prevent any extra power from being applied unintentionally.

3. Timely and precise small counteractions. If it starts porpoising, you need to do something, it won´t stop alone. Contrarily to the generic seaplane literature which says we need to slow down and not fight it:

This is what the FAA says:

If porpoising occurs due to a nose-low planing attitude, stop it by applying timely back pressure on the elevator

control to prevent the bows of the floats from digging into the water. The back pressure must be applied and maintained until porpoising stops. If porpoising does not stop by the time the second oscillation occurs, reduce the power to idle and hold the elevator control back firmly so the seaplane settles onto the water with no further instability.Never try to “chase” the oscillations, as this usually makes them worse and results in an accident.

I agree with this point, but we can only utilize this approach during training when we intentionally slow down to correct issues until the student acquires the necessary techniques. Once we become aerial firefighters, slowing down will significantly increase the distance required for scooping water, reducing the availability of scooping sites and therefore making our contribution less effective.

If I need to explain how I keep the nose steady or take over from a student who is struggling, which happens during the learning process 100% of the time, I describe it as follows:

In case scooping gets out of control, in most cases we will dump the load in a controlled manner and fly out of the water, and back to the air, our primary element as the aircraft we are. Staying down there with a loaded aircraft that won´t float on its MTOW, most likely will bring more issues.

Here is a good example of how hesitation and staying on the water did not end up that well:

4. Use your controls effectively, and anticipate stick inputs.

There is one way to fix this. Training with an instructor that will put you through it in a controlled environment.

We call it deliberate practice.

This exercise takes us through different speeds, weights, and power adjustments. And we can do it as many times as your arm can handle it if the area is long enough. A 3 to 5Km-long water body works great for this exercise

If a picture speaks a thousand words, a video must speak a million!

This is what this exercise looks like:

Scooping performance and advanced techniques

So now we should be able to understand that porpoising is not normal, and where could we improve.

If a picture speaks a thousand words, real videos with some text below explaining what goes on must speak a million! Here are a couple of videos of real scooping wrapping everything up.

What did we just see?

- Student mode vs high performance vs ineffective scooping

- Fast approach (our task works on water delivery rate), washing up speed during the turn.

- Quick touchdown technique (advanced)

- Fast scooping technique (advanced)

- Quick lift-off rolling into one float (advanced)

Advanced Techniques:

We won´t get deep today on advanced techniques, but here are some aspects to think about.

Safety-minded…but performance-driven.

It’s not one or the other:

- There is a difference in the performance of approximately 150% between a pilot that masters advanced techniques and a pilot that settles in the standard lower speeds – porpoising. (E.G: 1000m vs 2500m)

- This difference will affect scooping area suitability.

- Mastering techniques and acquiring extra finesse represent a safer operation in the long run.

- A sense of achievement and a feeling of progress is important to keep motivation and interest.

- When we get paid to perform a specific mission, it is our goal to perform it as safely and as effectively as we possibly can

But to be able to learn advanced techniques you need to be at an “Awareness stage” surrounded by the right team. Do not try on your own without adequate supervision.

Do not become a statistic:

The demand for Fireboss aircraft worldwide is soaring, but the shortcuts in training and mentoring we see sometimes are no laughing matter. Don’t become part of that! If you’ve been battling porpoising for a while, or see that it has become a standard in your organization, don’t settle or normalize it. Embrace it as a clear indicator of how much you and your organization have mastered the technique. Aim for a rock-solid nose, 10 out of 10 times in any water conditions, whether choppy (easier) or glassy (harder). And if you can’t fix it on your own, seek further training from a qualified and experienced instructor, inside or outside your organization to put you on the right path.

Remember that if we take it too far and push too much, we will also become a statistic. There have been a few accidents with this fleet to do with competitive behavior. This article, halfway through it, gets deep into competitive behaviors and their associated problems. This report from Canadian TSB is a must too in the same regard.

And a last thought…

The “sweet spot” not only refers to flying attitude and scooping.

There is a sweet spot here too! Pushing too hard will put your nose down, but pushing too hard too quick as amphibious scooper pilot will take your performance and reputation down too, and very quickly!

With 2024 just starting, let’s spread the message of safe and effective scooping, Together, we can make porpoising a thing of the past and ensure smooth, flawless water collection for all Fireboss pilots.

Feel free to share your thoughts, and experiences in the comments below.

Let’s keep safety conversations flowing!

Éder